Plague

Plague. An Introduction

Plague is a bacterial disease that is still common in rodents today. Scientists have studied the plague with a modern mindset since the late 19th century, when the Third Plague Pandemic started in earnest in southern China and India. One hundred twenty years later, our understanding of the disease is still advancing through efforts of both the natural sciences and the humanities.

As a result of a cross-disciplinary interest in plague, researchers have a wealth of sources to work with: from (ancient) DNA of the bacterium extracted from skeletons and biological tissue for the past 5,000 years to archaeological, written, and visual sources for the past 1,500 years, to surveillance records of plague in humans and in wildlife for the past 100 years. There are very few other (if any!) diseases that have comparable records from which to learn about all aspects of a disease.

European Reservoirs

I have worked on plague since 2010, publishing my first paper on the topic in 2012, dealing with our incomplete understanding of how plague persists within these reservoirs. After that paper, I started working with historical data, such as the compendium of plague outbreaks collected by Biraben in 1974, digitized by Ulf Büntgen et. al., and later improved upon by Fabienne Krauer and myself.

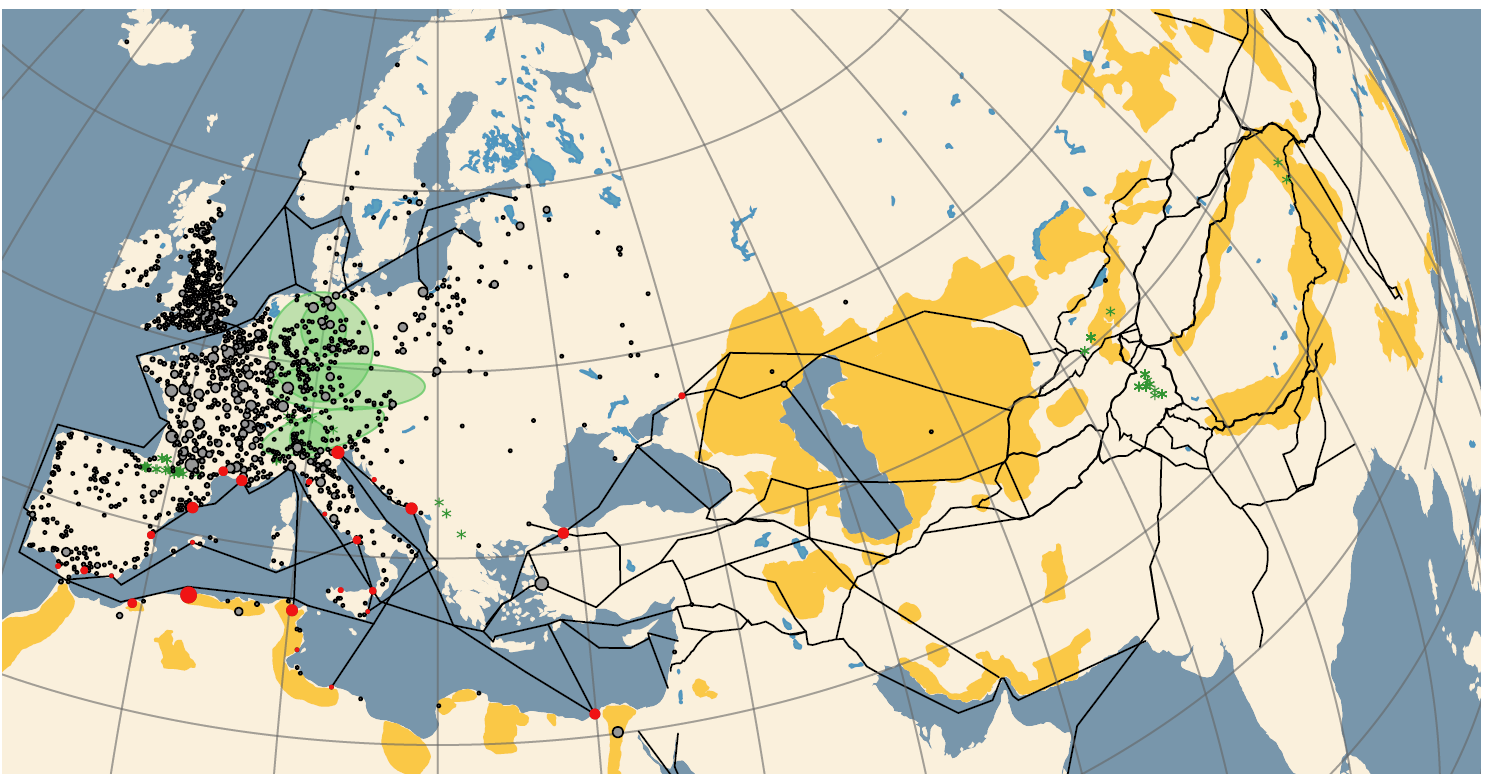

I used these compendiums of plague outbreaks to search for Europe's medieval plague reservoirs, looking for regions from which new plague outbreaks would radiate. One of the key insights of that paper was that plague appears to have been frequently imported into pre-modern Europe, appearing first in the harbors before moving inland. This was happening frequently enough that we concluded that Europe may not have needed a permanent wildlife reservoir of plague to explain the pattern of outbreaks we saw. I presented these results in 2013 at the Yersinia 11 conference in Suzhou, China (available here), and published the work in 2015 in a high-impact publication in PNAS.

Whether plague frequently invaded Europe from Central Asia or only at the start of pandemics, and whether a reservoir once existed in Europe are now both points of contention. It turns out that reconstructing the transmission routes of plague is a challenging problem, even with the help of phylogeographic maps based on ancient DNA samples from the plague.

Schmid, B.V. et al. (2012). Local persistence and extinction of plague in a metapopulation of great gerbil burrows, Kazakhstan, Epidemics, 4(4), pp. 211–218.

Büntgen, U. et al. (2012). Digitizing historical plague, Clinical infectious diseases: an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, 55(11), pp. 1586–1588.

Krauer, F. and Schmid, B.V. (2021). Mapping the plague through natural language processing. Epidemics 41.

Schmid, B.V. et al. (2015). Climate-driven introduction of the Black Death and successive plague reintroductions into Europe, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 112(10), pp. 3020–3025.

Eaton, K. et al. (2021). Plagued by a cryptic clock: Insight and issues from the global phylogeny of Yersinia pestis, Communications Biology 6, 23.

Transmission models

Besides studying plague reservoirs, I supervised a number of students who explored different ideas of how plague epidemics would transmit within the confined boundaries of a town or village.

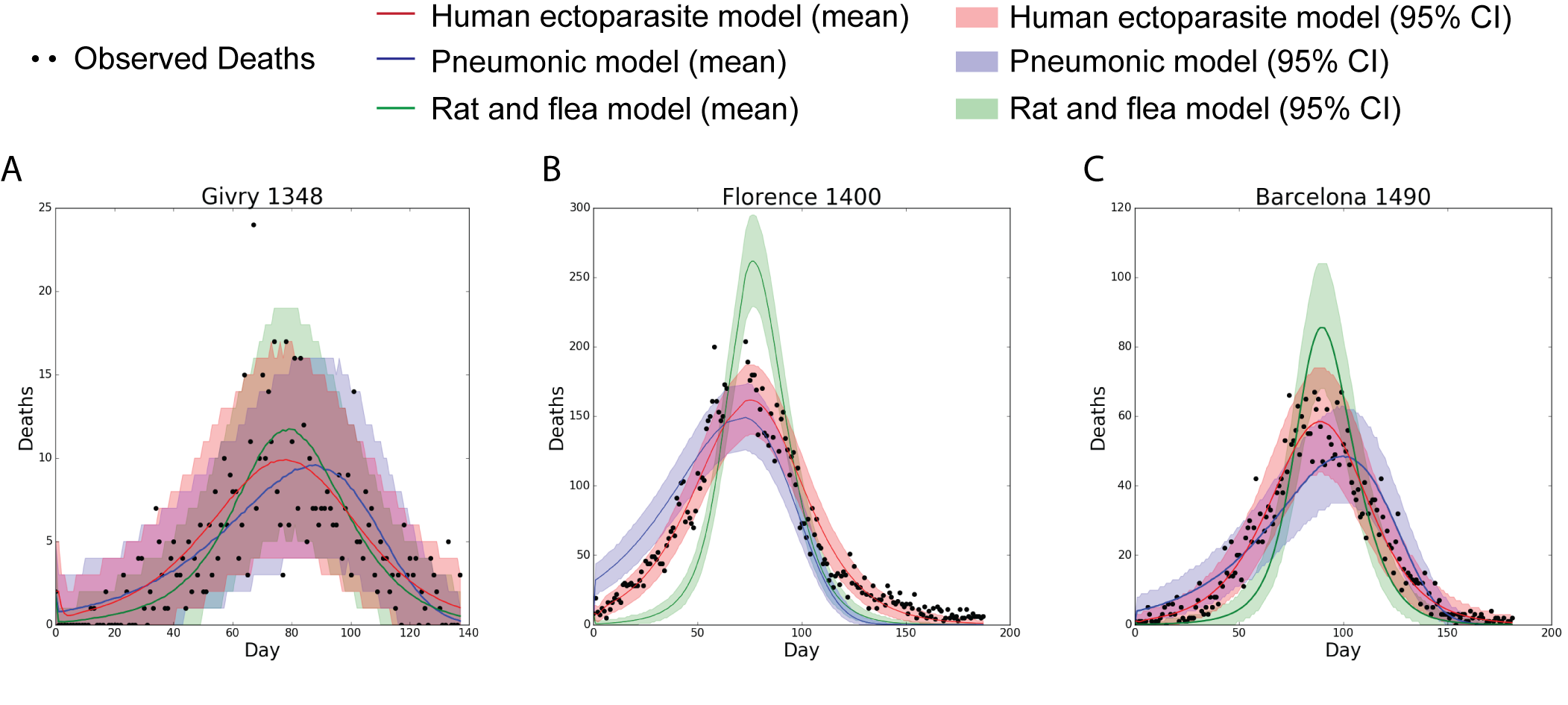

In one of these studies, we tested whether airborne plague, rat and flea-borne plague, or human vector-borne plague could best describe the observed epidemic curves of plague outbreaks in medieval and pre-modern times. During an excellent PhD project, Katharine R. Dean found that these outbreaks were best described by a human louse or flea vector that directly spread the disease between humans.

Dean, K.R. et al. (2018). Human ectoparasites and the spread of plague in Europe during the Second Pandemic, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 115(6), pp. 1304–1309.