How deadly was plague across history?

Most of the focus of plague has been on its infamous epidemics, like the Black Death in the mid-14th century where a large fraction of Europe died. But Yersinia pestis has been present among humans for centuries, and especially during the Third Pandemic caused outbreaks that were, while still severe by current-day standards, were far milder than the medieval outbreaks.

Plague as a bacterium has been a bit of a guinea-pig for the field of ancient DNA testing (which is a strange reversal of fortunes, as guinea pigs used to be the most sensitive way to test for the presence of plague, but that is another story), and as such, many historical skeletal remains from Eurasia are routinely tested for traces of the plague bacterium in their bones or teeth.

The best method I could think of to approximate how many people died of plague was to estimate the total number of people that lived (and died) across time and the fraction of those people that died of the plague.

The technical term for that fraction is cause-specific death rate, and there are a few ways to find it. The two methods I employ here are:

- Look at the fraction of people who carried plague in their bloodstream at their moment of death when there was no a-prior reason to assume they died of plague.

- Study records of mortality that were kept for long periods of time, to catch the average chance of dying of plague, and not just the chance of dying of plague during a plague epidemic.

tl;dr. My best-guess estimate is that ~20% of all mortality can be attributed to plague during the 1st and 2nd plague pandemic in the affected regions. That number drops to ~10% during the non-pandemic periods prior and between the 1st and 2nd plague pandemic.

For the third plague pandemic, southern China and India experienced a ~10% cause-specific death rate, while for the rest of the world this was <1%.

Historic descriptions of Plague & ancient DNA

The ability of paleogeneticists to recover DNA from long-dead remains (think Jurassic park, but then limited to the last 700,000 years), is having a profound impact on several fields of science and the humanities, including those of biology and history. One of those fields is tracking and understanding the impact of historic diseases. Prior to ancient DNA analysis, diagnosing a disease based on very minimal descriptions could be extremely challenging. The Plague of Cyprian 249-262 AD is a good example of such a challenging description:

This trial, that now the bowels, relaxed into a constant flux, discharge the bodily strength; that a fire originated in the marrow ferments into wounds of the fauces; that the intestines are shaken with a continual vomiting; that the eyes are on fire with the injected blood; that in some cases the feet or some parts of the limbs are taken off by the contagion of diseased putrefaction; that from the weakness arising by the maiming and loss of the body, either the gait is enfeebled, or the hearing is obstructed, or the sight darkened

People have been trying to make sense of that description for a long time, and there is still no consensus. Suggestions range from smallpox to measles to a hemorrhagic fever such as Ebola.

Whenever paleogeneticists can extract ancient DNA of the bacterium of virus from a skeleton, they immediately provide clarity on what pathogen was present in the body at the time of burial. There are some small caveats, such as contamination of the sample with modern variants of the disease, but those tend to be easily discovered and excluded.

Orlando, L. et al. (2013) ‘Recalibrating Equus evolution using the genome sequence of an early Middle Pleistocene horse’, Nature, 499(7456), pp. 74–78.

'The Plague of Cyprian', retrieved 23 july 2023 from Wikipedia.

The extraction of plague DNA from corpses

Now, to the plague. The first thing you need to know is that plague has been killing people for at least 5,000 years. Ancient DNA studies of human remains have found plague across Eurasia, in a surprising large fraction of the corpses that were tested.

I kept a record of all ancient DNA plague studies that came out up until August 2023, and of the 759 corpses that were tested for plague, 45 were positive! That suggests that a remarkable 6% of all human remains tested were positive for plague. And given the nature of the disease, we can be sure that when you have plague circulating in your bloodstream at the moment of your death, then your cause of death is plague.

Importantly, these corpses are not only corpses that died under suspicious circumstances (like a mass burial events), but also individual graves, and the difference in plague-specific death rate between the two groups is minimal (5.7% when excluding mass burials, 5.9% when including mass burials). If you want an estimate for the uncertainty on that 6% - resampling the 10 observations many times will get you a 95% confidence interval of 3.7%-10.4%.

So for the period of 3,500 BC to 541 AD, we have a cause-specific mortality rate estimate for plague of 6% of all deaths. We stop at 541 AD because in 542 AD we have the first known plague pandemic starting, and if you sample human remains during a known pandemic plague event, it is not surprising to find a high cause-specific mortality rate for plague.

And indeed, we can see evidence of that higher rate when we tally up the fraction of plague-positive samples in a large study by Keller et al. (2019) on the First Plague Pandemic. Keller finds plague in 34 / 183 samples across 19 sites, suggesting an 18.6% cause-specific mortality rate for plague. Even when we remove the three sites which could be linked to mortality events, we are still left with a cause-specific mortality rate for plague of 15.2%.

So, if we ignore different sampling biases, then our first-order approximation is that during the 1st Plague Pandemic, the cause-specific mortality rate of plague, as established by ancient DNA paleogenomics, is three times higher than during the three millennia before.

Two similar studies during the Second Plague Pandemic are those of Eaton et al. (2023) in Denmark, and Keller et al. 5 across Europe. Eaton et al. (2023) finds 13 plague positive samples / 298 samples tested across 13 sites, resulting in a cause-specific mortality rate for plague of just 4.4%. Keller et al. (2023) finds 11 plague positive samples / 89 samples tested across 6 sites, which results in a cause-specific mortality rate of 12.4%.

One thing to note is that even in plague burial sites, the success rates of finding plague DNA from a sample is not 100%. Keller looked at 5 burial sites that were linked to plague outbreaks, and finds plague in 15 / 29 samples, a cause-specific mortality rate of 51.7%. Immel et al. (2021) finds plague in 25 / 30 samples tested (83%). Seguin-Orlando et al. (2021), and Guellil et al. (2021) report only 2/15 (13.3%) and 3/15 (20%) individuals from a plague burial site to be plague-positive.

One reason why not all corpses in a plague burial site yield the plague bacterium is that people that died of other causes than plague might still end up buried in these plague burial sites. Another reason are differences in the preservation quality of the samples - hot and humid but oxygen-exposed places can be particularly tough on ancient DNA. aDNA groups also differ in their methods and the amount of budget that they are willing to spend on retrieving aDNA from the samples. Given all that, we should probably treat these percentages as lower-bounds (although you have to be alert to preferential sampling from mass burial sites, as that would work the other direction and inflate the percentage).

Keller, M. et al. (2019) ‘Ancient Yersinia pestis genomes from across Western Europe reveal early diversification during the First Pandemic (541-750)’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 116(25), pp. 12363–12372.

Eaton, K. et al. (2023) ‘Emergence, continuity, and evolution of Yersinia pestis throughout medieval and early modern Denmark’, Current biology: CB, 33(6), pp. 1147–1152.e5.

Keller, M. et al. (2023) ‘A Refined Phylochronology of the Second Plague Pandemic in Western Eurasia’, bioRxiv.

Immel, A. et al. (2021) ‘Analysis of Genomic DNA from Medieval Plague Victims Suggests Long-Term Effect of Yersinia pestis on Human Immunity Genes’, Molecular biology and evolution, 38(10), pp. 4059–4076.

Seguin-Orlando, A. et al. (2021) ‘No particular genomic features underpin the dramatic economic consequences of 17th century plague epidemics in Italy’, iScience, 24(4), p. 102383.

Guellil, M. et al. (2021) ‘Bioarchaeological insights into the last plague of Imola (1630-1632)’, Scientific reports, 11(1), p. 22253.

Plague as fraction of deaths in various Bills of Mortality

The Second Plague Pandemic was fairly brutal. Besides wiping out half of Europe to start with (the usual estimate is 30-60%), the disease also kept recurring for the next 400 years in Western Europe, and up to 600 years in the Anatolia region.

There are a number of datasets out there that help us get a handle on the death toll. First, Curtis and Roossen looked at the period of 1349-1450 in the Low Countries (roughly equivalent to the Netherlands and western Belgium), where they documented the deaths per year during plague years and non-plague years. A little bit of math to calculate the additional deathtoll of plague and the number of plague years gives a disturbingly high all-cause mortality attributable to plague of 23% in urban settings and 38% in rural settings!

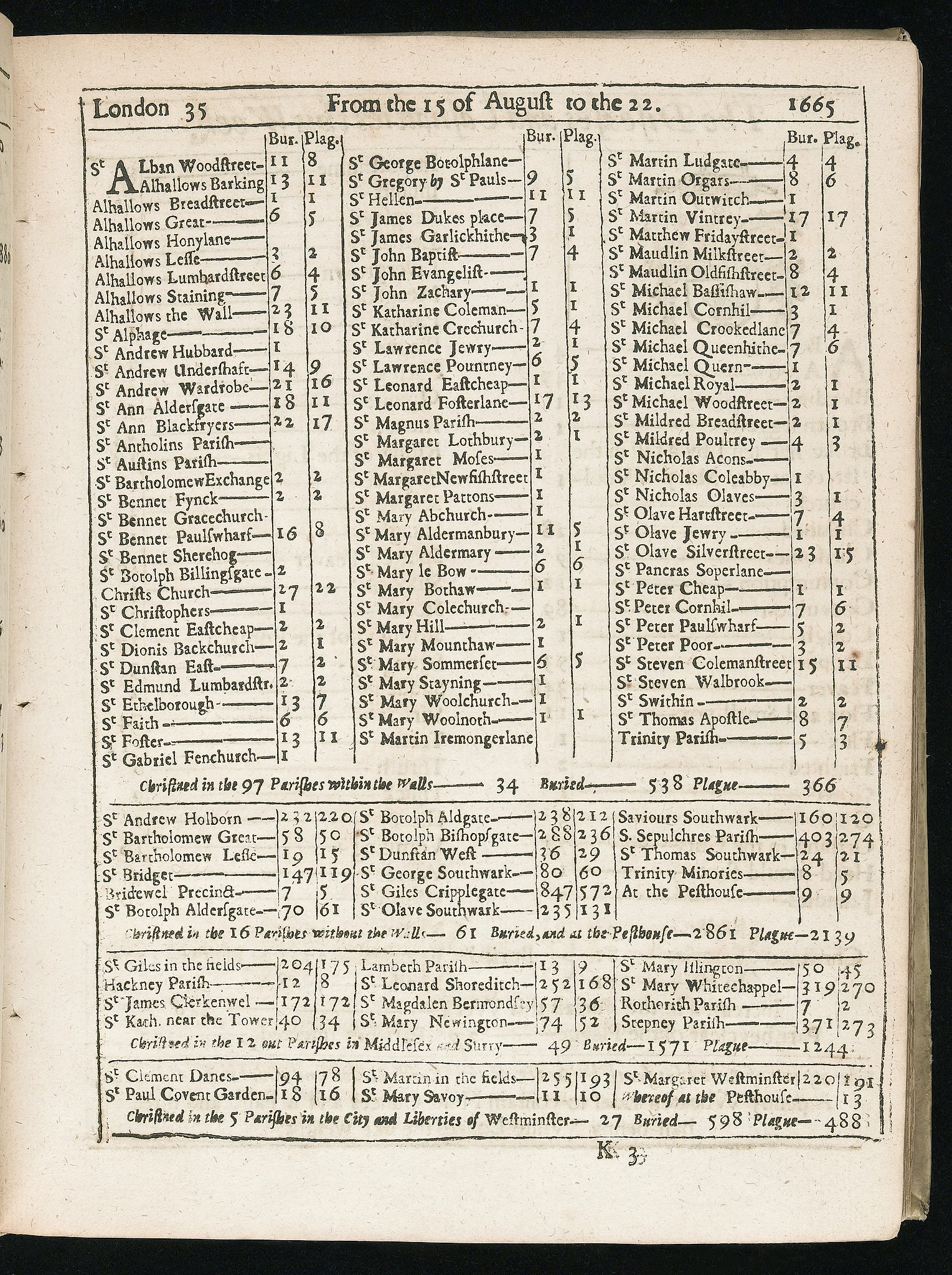

We can do a second check, using the London bills of Mortality, recently analysed by David Earn. For the 1331 weeks between 1577 and 1666, the bills list a total of 451,365 deaths, of which 200,465 are reportedly caused by plague. That amounts to a staggering 44% of all deaths being caused by the plague.

These numbers are high, and have a substantial error margin (for example, diagnosing the cause of death during plague outbreaks was outsourced to unskilled labor - thank you, Daniel Curtis for alerting me to that), and both London and the Low Countries had exceptionally high population densities, which may have contributed to the intensity of the plague outbreaks.

These numbers are substantially higher from the 4.4% that Eaton (2023) reported and the 12.4% reported by Keller (2023), although the 23% is not that far off from the 18.6% that Keller (2019) reported for the first plague pandemic.

[BOOK] Nükhet Varlık. Empire, Ecology, and Plague: Rethinking the Second Pandemic (ca.1340s–ca.1940s). (upcoming).

Curtis, D.R. and Roosen, J. (2017) ‘The sex-selective impact of the Black Death and recurring plagues in the Southern Netherlands, 1349-1450’, American journal of physical anthropology, 164(2), pp. 246–259

11

Earn, D.J.D. et al. (2020) ‘Acceleration of plague outbreaks in the second pandemic’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 117(44), pp. 27703–27711.

Conclusion

So, how deadly was the plague in historic times? We have a lower-bound estimate provided by ancient DNA retrieval of the bacterium from corpses, which is especially useful when sampled from skeletons that are not linked to known plague burial sites. And we have what is probably an upper-bound estimate provided by various tax records and bills of mortality historic records. These records (by definition) don't exist for prehistoric sites, but they do exist from the Second Plague Pandemic onwards.

Roughly speaking, we have a lower-bound 6% of the pre-historic deaths that we can attribute to plague in Europe and Central and western Asia, which may translate into ~10%, given that ancient DNA doesn't catch all plague cases. The cause-specific mortality rate estimated by aDNA increases to 18% during the First Plague Pandemic for Europe. We don't have many written quantitative records, but let's put the First Plague Pandemic on the same footing as the Second Plague Pandemic at ~25% (see below).

For the Second Plague Pandemic we have mixed signals - ancient DNA gives us 4.4% and 12.4%, of which I am tempted to trust the latter to be closer to the truth given all the ways that ancient DNA research can underestimate the actual cause-specific mortality rate. We also have historic records that put the cause-specific mortality rate of plague considerably higher at 23-44% (but these records can easily be an over-representation - a risk I think is particularly true for the Bills of Mortality, where diagnosing the death was left to the poor). If I had to pick a percentage, then ~25% does not seem unreasonable given how frequent (roughly once every 40 years) larger plague epidemics swept across Europe and how often minor plague epidemics happened in between.

The aDNA percentages that I provide in this blog post are listed in greater detail in this excel sheet.